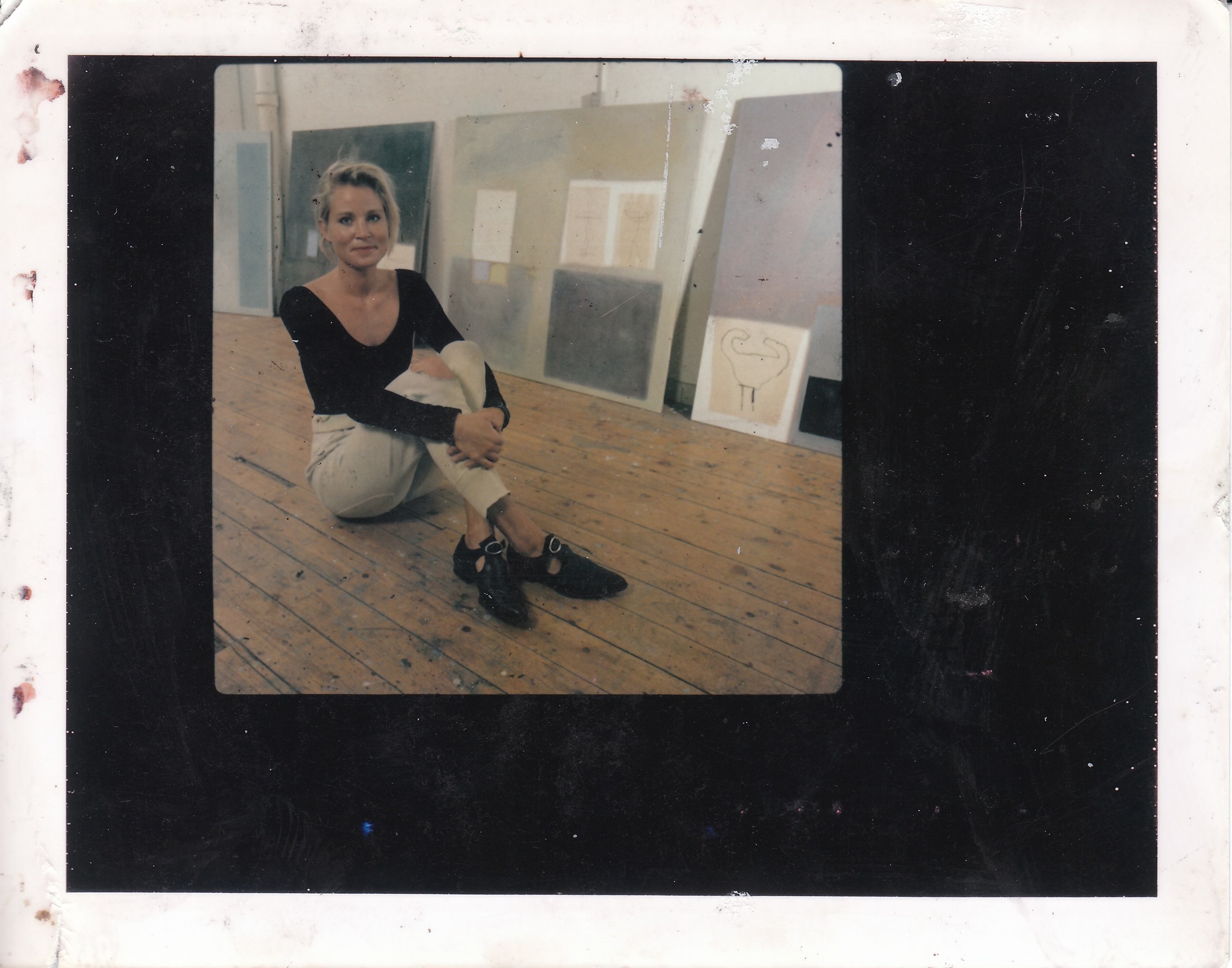

A conversation with BIRGITTE LUND

On mapping and becoming — the art of continual excavation

“If you view your life like you would a map, from above, it’s always very strange, looking down. Seeing how things work out, or don’t, or how one thing leads to another, or doesn’t.”

My first meeting with Birgitte Lund left me turning over the usual suspects of art criticism: “Art doesn’t need to be explained.” “The artist should get out of the way.” “Concept shouldn’t define the medium.” All constructs Birgitte contradicts, and ones I’ve never wholly agreed with. Even less so after learning how she works. “Like an archaeologist, but in reverse order,” she says.

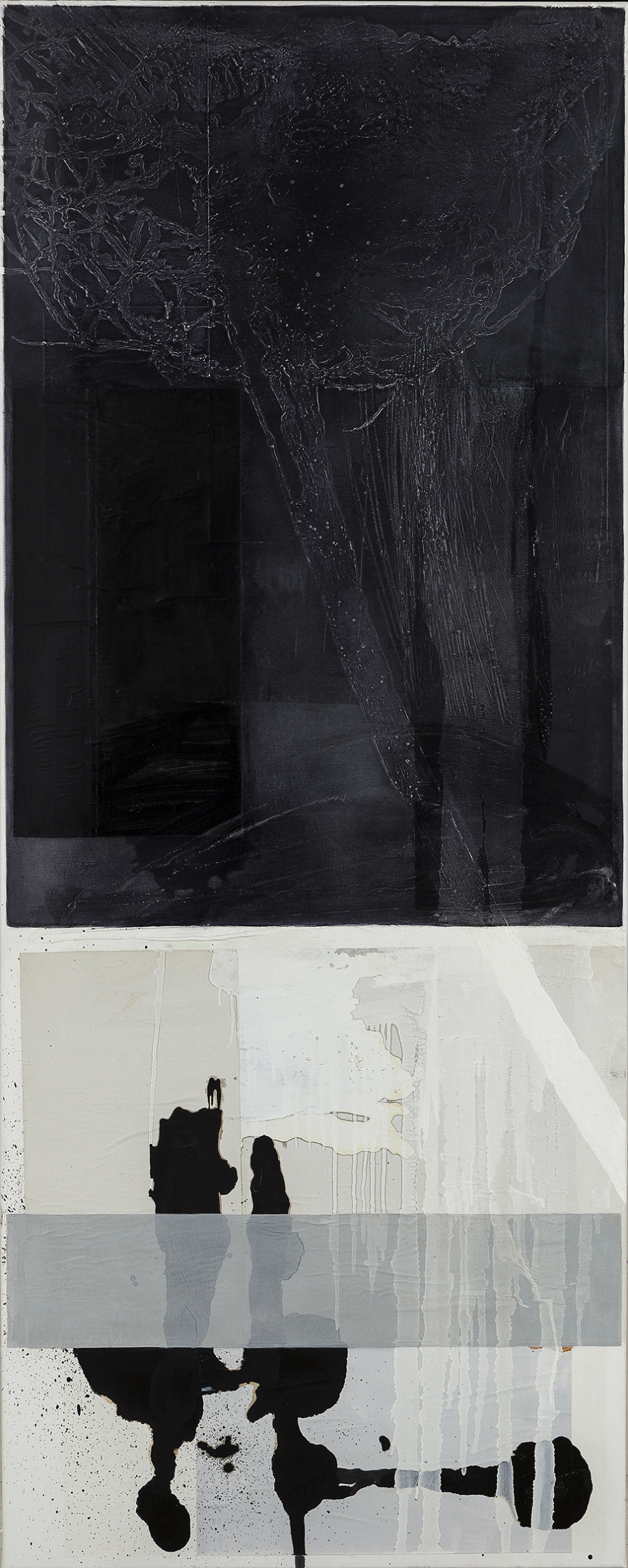

Birgitte Lund’s work is a science in the interrogation of space and material, each piece their very own petri dish, framing microcosms of mixed-media that develop beyond first sight. Acrylic, paper, liquid rubber, ash, clay, plants and flowers, from corner to corner, she is mapping territories, building new landscapes. Pass simply as “beautiful” and you’d be seeing only the surface.

“I like to explain my process of building up a piece, and if that adds something for you, that’s wonderful,” Birgitte says. “But I prefer to think I build the terrain, I don’t draw the route for how you should experience it.

To categorize Birgitte’s work as “Abstract” or “Abstract Expressionism” would be correct but also reductive. Cartographic Expressionism would be more appropriate.

Birgitte Lund grew up in Ballerup, Denmark, and at the age of twelve moved with her family to Espergærde, once a small fishing village just thirty minutes north of Copenhagen. “Having the sea next to you, it just goes into your system, I will forever be drawn to being near it, no matter the weather” she says.

Her path to becoming an artist wasn’t an obvious one. “Even though my dad was an architect, I wasn’t fed with art or culture like that growing up. My way of moving around this ‘life map,’ as I see it, was intuitive. I always seemed to have a strength and conviction in my direction, sometimes even more so than I have now at sixty-six. It was as if I knew where I was going, but I wasn’t influenced by family, teachers, or art shows, or anything like that…” Pausing for a moment, she starts again, “There was an inner urgency to express emotions through painting and drawing, as though the act itself already had a plan for me.”

She grew up with three brothers, one older and two younger, in what she describes as a “very male household.” “We would fight all the time, and at that point in history, expressing emotions wasn’t encouraged. 'Never cry' it was all about toughen up and move on.”

Her parents however, were quietly supportive, “Warmhearted and loving” Birgitte describes them as. “No matter what I chose in life, they never asked questions like, ‘Is this good for you?’ or ‘Can you live from this?’ They sensed that if I was happy, things were right. Trust, for me that is true love, and the most beautiful thing you can give your children.”

When I ask how this inherent intuition has informed her past decisions, she smiles. “My personality is also very influenced by provocation and insisting on doing things my own way. If people tell me, ‘Do not do this,’ or ‘You can’t do this,’ I’ll have an urge to do exactly that.”

This spirit of defiance showed up early in her education. “Everyone told me, ‘You should go to the Royal Academy if you want to be a painter.’ The snobbery around aspiring artists not being taken seriously if they went to the Design School only made me more intrigued. So instead of booking a tour as you should, I just went in, and explored on my own without any appointment.”

This was 1978. Birgitte was only nineteen, and at that time the Danish Design School was located at Israels Plads in Copenhagen, just across from the food market, Torvehallerne. She remembers wandering up to the fifth floor and discovering the weavers’ department, “Rows of yarns, hundreds of colors, all lined up in metal cabinets. I was stunned. I had no prior interest in weaving; I was simply drawn to the color.” From there, she drifted into the print department. “Experimentation was a large part of the Danish Design School back then; there was an incredible air of freedom. You could almost do anything there. Printing frames, silkscreens, big buckets of paint, people in stained work clothes, I just loved it. Even though I didn’t know a thing about printing, silk-screen, or textiles, I knew instantly: this was my place.”

A few months later, she was admitted, one of just sixteen accepted out of six hundred applicants. “She’s so weird and wild, totally unpredictable” Birgitte laughs, recalling how she believed one professor saw her. When I asked her why she thought this, Birgitte explained that she brought “a van full of large-scale paintings to the admission committee,” whereas other applicants brought “small elegant portfolios”. She remembers how the professors of the admission committee also tried to scare her away, talking about all the uncertainties of living a life as an artist, even saying she was too young. “I guess they were testing my defiance and resilience, but of course, this only made me more determined to pursue my place.”

Freedom, independence, spontaneity is what she wanted. From 1977 - 1988 (age 18 - 29) she had commitment, partnership, and predictability. A reality some people only dream of, but never find. Birgitte was standing in front of love, knowing it was holding them both back.

“I had always dreamt of a more ‘experimental’ and free life,” Birgitte says, adding quotations over experimental. “The word ‘bohemian’ is a strange way to express it, but that I believe is what I was searching for. A place in time where I didn’t know what was around the corner.”

We spoke of the stripping back, dismantling, and at times, necessary pain required to get to the core of what you’re trying to express, or find. This isn’t about “the tortured artist,” it's the question of whether security can slow the “finding” of self or evolution towards the truest form of expression. Creating the necessary tensions needed to create is challenging with a safety net. Love can be freedom, but it can also be a trap.

Birgitte speaks of 1988 as a “magical year” and the first year where she “finally felt free to focus” on her work. After her first big break-up, she mounted a solo exhibition within months, “It was like a revelation,” she says. When the contract for the exhibition was signed, she recalls “rushing straight back to my studio to paint over all the work I had created over a long period of time,” which was a radical break from the artist she had been.

“I felt so strongly that a whole new beginning was necessary.”

Birgitte created fifteen large-scale paintings built from layers of white, with asphalt, gold, and flashes of almost fluorescent blue, the asphalt acting like calligraphy across the surface. It was the beginning of what would become her signature approach: works constructed in multiple layers of texture and material, building new "landscapes" on canvas.

All of the paintings were sold out but there are no photographs of them or the exhibition. The exhibition took place in the well known Gallery Marius in Gothersgade, central Copenhagen. At this time, “this particular gallery was very experimental” Birgitte says.

Agnes Martin once said “The best things in life happen to you when you’re alone.” You don’t need to be an artist to pause, or be affected by that line. Any person with the luxury of memory can look back at the importance that long bouts of solitude bring. Up until this point, Birgitte’s fondest and most productive periods as an artist was her time spent in Paris in the late 80s, India in the early 90s, and when she moved to New York in 2001. Each time independently.

“If you keep doing your own thing while in a relationship, you have to have a very strong base in order to keep that up and want to come back to each other.”

Finding someone to stand still with, when you find it hard to stand still yourself, remains both trite and true. The paradox is that only time and reflection can teach you to recognise that primal pull, yet recognition alone doesn’t tame it. It lives inside you, something instinctive that can only ever be softened, never solved.

Before meeting her husband in 1998, “I had ten years of going wild in Copenhagen… painting, creating exhibitions, dating… after this time I was ready to commit and felt the urge to give and share love. At this point I was still living in Christianshavn and working at the Café Wilder. My studio was in Nørrebro near Empire Bio which was a very rough area at that time. I had no money, but I still managed to live a great life and felt free. I was spending all of what I earned working at Cafe Wilder on art supplies and travelling to India, my lifelong inspiration, as often as I could.”

“I met my husband fairly late in life. I was thirty-eight. It was a very happy coincidence. Before then I always saw myself as a traveler of the world. As soon as I met him though, I knew this type of love was porous enough to give me the freedom I needed to do my work.”

Returning to Birgitte’s instinctive way of “knowing her direction” and “moving with intuition,” that same quiet conviction resurfaced decades later in her 2018 series “The Subtlety within the Obvious”, a title that couldn’t be more fitting. The twenty-one large-scale works continue her exploration between order and instinct, between what is visible and what is concealed.

When I ask Birgitte if there’s a certain series of work that speaks to this directly, she says “It’s hard to say, every series represents a certain period of my life, whether that’s happiness or hardships.” In her 2012 series “Psychedelic Landscapes” she says “I am more bold in choice of color and figuration,” whereas in “The Subtlety Within the Obvious” she says, “It’s all there, but more hidden, dimmed under layers of glazing.”

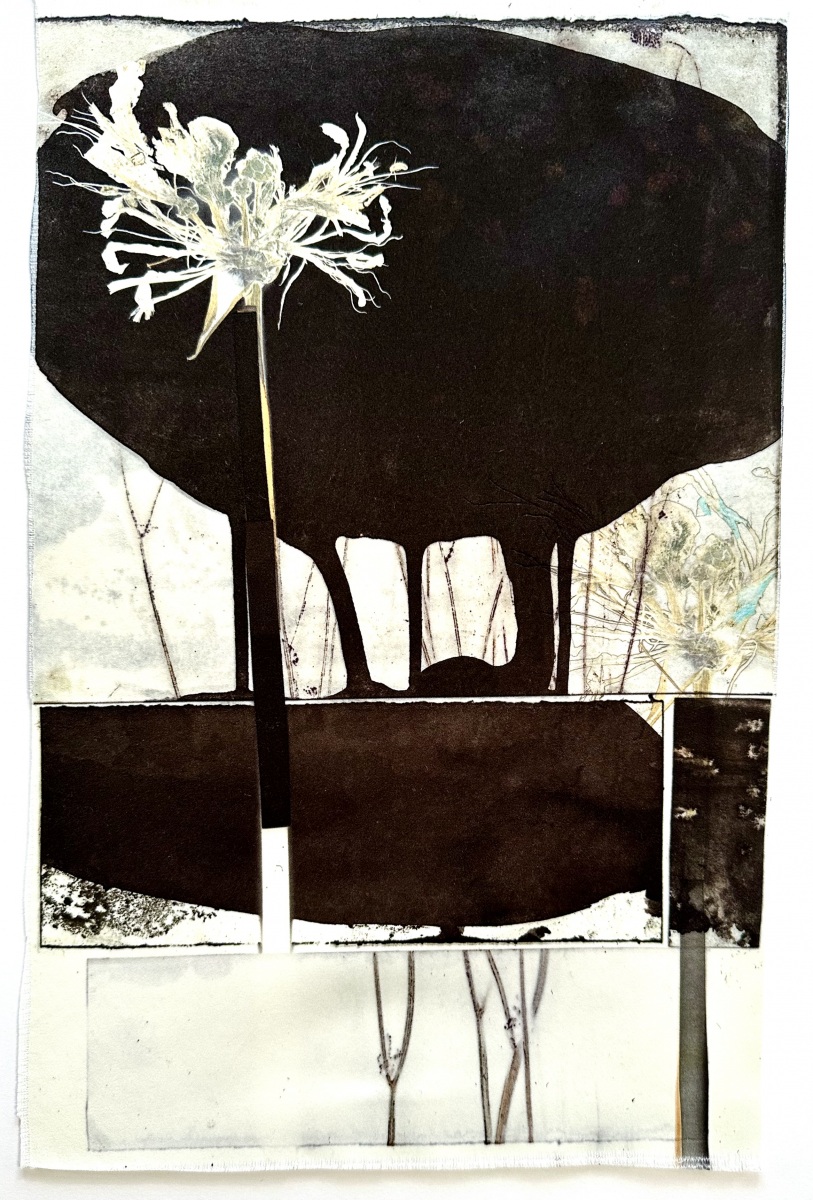

Her latest series, “The Spirit of Strange Flowers” which started in 2021 and continues today, four years later, brings her closer to her natural rhythm of searching and discovery. “Bold and outspoken” and an “ongoing conversation between nature and myself.” Pieces made up of pressing plants and flowers into thick silk, each piece entirely unique, made through a process known only to her.

Although a large body of her work is in response to her years in New York, “fascinated, captivated and overwhelmed by the bombardment of color and vertical lines” for me, her work has become a continuous reminder of Danish culture. Similar to Birgitte’s process of “dis-excavating” her work - piecing together to form a clearer picture - it’s rare to find a Dane who will unravel a story about themselves without being prompted. You need to return again and again, “excavate” with curiosity, and have patience with their pace of unfolding.

“People are always talking about whether you’re introverted or extroverted. I know I’m extroverted, but there are times I need to disappear into my studio and be alone. I can be very private about my work, though I’m learning to show pieces before they’re ready. But sharing the process too soon can make it lose its life, opinions, even well-meant ones, can shift how I see it, how I move forward.”

“Sometimes when I look at older work, it’s a nice feeling that I can still stand behind certain pieces. I am not self-praising, or anything, but I am simply appreciative of what I could do at the time…”

I ask Birgitte about her relationship to time, and to the body of work she’s created so far. “Hopefully I continue evolving. This is the process that is so interesting. If this was my life expression and I was dying, I could say I did my best, 120%. I’m meticulous, almost a perfectionist, and very hard on myself, self-critical, more than most would think. What you see, and what I show you, I’m content and happy with. But I hope it’s not the end. I want to keep going, figuring things out, going into the microscopic world of how I build up my work. Keep on digging.”

Seen in “The Spirit of Strange Flowers” it’s clear Birgitte isn’t slowing down, she is accelerating. “The Spirit of Strange Flowers” feels more like an open invitation, one that will speak both to her standing audience, while evoking a new generation to take notice.

She pauses, reflecting on what’s next. “At the moment I’m thinking about what I’ll do in the next few years, and I think it’s going to go deeper and deeper into the details. I’m fascinated by what happens below all the layers… This is a long lasting passionate affair” she says, a sentiment that’s not subtle, but an obvious reminder that her boldest chapters are still ahead.

“I feel free,” she finishes.